lambdaisland / Trikl

Programming Languages

Trikl

"Terminal React for Clojure" => Trikl

Trikl is a long-term slow moving research project. It is not intended for general consumption. There are useful bits in there, but expect to get intimately familiar with the implementation if you want to get value out of them.

The README below is from the first incarnation of Trikl, which had severe shortcomings around event handling and how it handles components. The groundwork for a new version has started in the lambdaisland.trikl1.* namespaces.

Regal is a spin-off library created to support this work.

Trikl lets you write terminal applications in a way that's similar to React/Reagent. It's main intended use case is for hobbyist/indy games.

With Trikl you use (a dialect of) Hiccup to create your Terminal UI. As your application state changes, Trikl re-renders the UI, diffs the output with what's currently on the screen, and sends the necessary commands to the terminal to bring it up to date.

This is still very much work in progress and subject to change.

Example

You can use Trikl directly by hooking it up to STDIN/STDOUT, or you can use it as a telnet server. The telnet server is great because it makes it easy to try stuff out from the REPL.

For instance you can do something like this:

(require '[trikl.core :as t])

;; store clients so we can poke at them from the REPL

(def clients (atom []))

;; Start the server on port 1357, as an accept handler just store the client in

;; the atom.

(def stop-server (t/start-server #(swap! clients conj %) 1357))

;; in a terminal: telnet localhost 1357

#_(stop-server) ;; disconnect all clients and stop listening for connections

;; Render hiccup! Re-run this as often as you like, only changes are sent to the client.

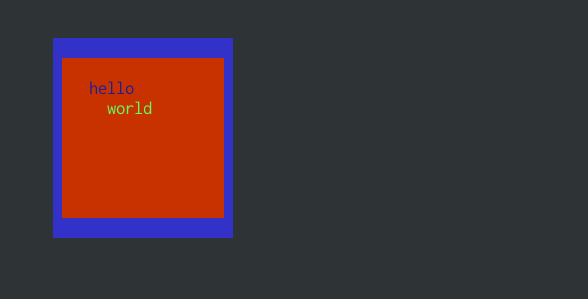

(t/render (last @clients) #_(t/stdio-client)

[:box {:x 10 :y 5 :width 20 :height 10 :styles {:bg [50 50 200]}}

[:box {:x 1 :y 1 :width 18 :height 8 :styles {:bg [200 50 0]}}

[:box {:x 3 :y 1}

[:span {:styles {:fg [30 30 150]}} "hello\n"]

[:span {:styles {:fg [100 250 100]}} " world"]]]])

;; Listen for input events

(t/add-listener (last @clients)

::my-listener

(fn [event]

(prn event)))

Use stdio-client to hook up the terminal the process is running in.

Result:

Things you can render

You can render the following things

String

A string is simply written to to the screen as-is. Note that strings are limited to their current bounding box, so long strings don't wrap. You can use newlines to use multiple lines.

(t/render client "hello, world!\nWhat a lovely day we're having")

Sequence

A seq (so the result of calling list, map, for, etc. Not vectors!) will

simply render each item in the list.

(t/render client (repeat 20 "la"))

Elements

Elements are vectors, they contain the element type (first item in the vector), a map of attributes (optional, second element in the vector), and any remaining child elements.

Trikl currently knows of the following elements.

:span

A :span can be used to add styling, i.e. foreground and background colors. Colors

are specified using RGB (red-green-blue) values. Each value can go from 0 to

255.

(t/render client [:span {:styles {:fg [100 200 0] :bg [50 50 200]}} "Oh my!"])

:box

The :box element changes the current bounding box. You give it a position with

:x and :y, and a size with :width and :height, and anything inside the

box will be contained within those coordinates.

If you don't supply :x or :y it will default to the top-left corner of its

surrounding bounding box. If you omit :width and :height it will take up as

much space as it has available.

You can also supply :styles to the box, as with :span. Setting a :bg on

the box will color the whole box.

Note for instance that this example truncates the string to "Hello,", because it doesn't fit in the box.

(t/render client [:box {:x 20 :y 10, :width 7, :height 3} "Hello, world!"])

:line-box

A :line-box is like a box, but it gets a fancy border. This border is drawn on

the inside of the box, so you lose two rows and two columns of space to put

stuff inside, but it looks pretty nice!

By default it uses lines with rounded corners, but you can use any border

decoration you like by supplying a :lines attribute. This can be a string or

sequence containing the characters to use, starting from the top left corner and

moving clockwise. The default value for :lines is "╭─╮│╯─╰│"

(t/render client [:line-box {:x 20 :y 10, :width 10, :height 3} "Hello, world!"])

:cols and :rows

The :cols and :rows elements will split their children into columns and rows

respectively. If any of the children have a :width or :height that will be

respected. Any remaining space is distributed equally among the ones that don't

have a fixed :width/:height already.

So you could divide the screen in four equally sized sections using:

(t/render (last @clients)

[:cols

[:rows

[:line-box "1"]

[:line-box "2"]]

[:rows

[:line-box "3"]

[:line-box "4"]]])

Custom Components

You can define custom components by creating a two-argument function, attributes and children, and using the function as the first element in the vector. You can return any of the above renderable things from the function.

(defn app [attrs children]

[:rows

[:line-box "Hiiiiii"]

[:line-box {:height 15 :styles {:bg [100 50 50]}}]])

(t/render client [app])

App state

If you keep your app state in an atom, then you can use render-watch! to

automatically re-render when the atom changes.

(def app-state (atom {:pos [10 10]}))

(t/render-watch! client

(fn [{[x y] :pos} _]

[:box {:x x :y y} "X"])

app-state)

(swap! app-state update-in [:pos 0] inc)

(swap! app-state update-in [:pos 1] inc)

(t/unwatch! app-state)

Querying the screen size and bounding box

During rendering you can use t/*screen-size* and t/*bounding-box* to find

the current dimensions you are working in. There's also a (box-size) helpers

which only returns the [width height] of the bounding box, rather than [x y width height]. This should greatly alleviate the need to write your own drawing

functions, as you can now do everything with custom elements and a combination

of [:span ...] and [:box ...]. The main reason to write custom drawing

functions would be for performance, when what you are drawing does not easily

fit in the span/box paradigm. If you find yourself creating a span per character

then maybe a custom drawing function makes sense.

Custom drawing functions

To implement custom elements, extend the t/draw multimethod. The method takes

two arguments, the element (the vector), and a "virtual screen". Your method

needs to return an updated version of the virtual screen.

The main reasons to do this are because this gives you access to the current screen size (bounding box), and for performance reasons.

The VirtualScreen has a ":charels" key (character elements, analogues to

pixels), This is a vector of rows, each row is a vector of "charels", which have

a :char, :bg, :fg key. Make sure the :char is set to an actual char,

not to a String.

After drawing the virtual screen is diffed with the previous virtual screen to figure out the minimum commands to send to the terminal to update it.

(defmethod t/draw :x-marks-the-spot [element screen]

(assoc-in screen [:charels 5 5 :char] \X))

Things to watch out for:

-

Normalize your element with

t/split-el, this always returns a three element vector with element type, attribute map, children sequence. -

Stick to your bounding box! You probably want to start with this

(let [[_ attrs children] (split-el element)

[x y width height] (apply-bounding-box attrs screen)]

,,,)

You should not touch anything outside [(range x (+ x width)) (range y (+ y height))]

- If your element takes

:styles, then usepush-stylesandpop-stylesto correctly restore the styles from a surrounding context.

True Color

In theory ANSI compatible terminals are able to render 24 bit colors (16 million shades), but in practice they don't always do.

You can try this snippet, if you see nice continuous gradients from blue to purple then you're all set.

(defn app [_]

[:box

(for [y (range 50)]

[:span

(for [x (range 80)]

[:span {:styles {:bg [(* x 2) (* y 2) (+ x (* 4 y))]}} " "])

"\n"])])

iTerm and gnome-terminal should both be fine, but if you're using Tmux and you're not getting the desired results, then add this to your ~/.tmux.conf

set -g default-terminal "xterm-256color"

set-option -ga terminal-overrides ",xterm-256color:Tc"

Using netcat

Not all systems come with telnet installed, notably recent versions of Mac OS X

have stopped bundling it. The common advice you'll find is to use Netcat (nc) instead, but these two are not the same. Telnet understands certain binary codes to configure your terminal, which Trikl needs to function correctly.

You can brew install telnet, or in a pinch you can use stty to configure

your terminal to not echo input, and to enable "raw" (direct, unbuffered) mode.

Make sure to invoke stty and nc as a single command like this:

stty -echo -icanon && nc localhost 1357

To undo the changes to your terminal do

stty +echo +icanon

Graal compatibility

Trikl contains enough type hints to prevent Clojure's type reflection, which makes it compatible with GraalVM. This means you can compile your project to native binaries that boot instantly. Great for tooling!

License

Copyright © 2018 Arne Brasseur

Licensed under the term of the Mozilla Public License 2.0, see LICENSE.